Since the birth of the blog earlier this year, I'd be disingenuous to not reveal that one of my great hidden pleasures for starting it was the long-awaited opportunity of finally sharing my year end favorites lists in proper written form in a similar vein of all the critics and writers I passionately look up to most. Maybe it's some kind of egotism needing to be scratched or a self fulfilling compulsive exercise, but getting to publicly reflect on and share my most treasured findings brings me a many unbridled joy. Now, I'm also aware that my influence (if that's even a thing) is incredibly minimal to the endless sea of minds in the online cinephile community, but I'd like to think that by sharing these, that it pushes the needle on some of these more unknown titles, even if just by one account. There still remains a vast frontier of cinema to be discovered and canonized, so I hope to be a part of that collective reappraisal. With my introduction out of the way, here is the first of two year end lists, covering films I watched for the first time in 2020, that premiered in 2018 and prior. Hope you find something new.

10) BROUILLARD - PASSAGE 14 (2013) (Dir. Alexandre Larose)

The sole avant-garde/video installation piece on this list, Canadian filmmaker Alexandre Larose's 10 minute long environmental spectacle is a scattershot traversal through a lush patch of land situated in and around a family cottage nestled in the Quebecoise region. Utilizing layering manipulation from multiple in-camera documents, Larose presents a hypnotic dreamscape that reimagines the notion of the actualite' as a metaphysical manifestation of space, time, and memory. A binded passage outside the limitations of our bodies' sensory reception. It related to me as a hypothetical illustration of the afterlife (based on more scientifically backed abstraction of what that'd even be like). Removed of the organic shell, energy and consciousness fade into a harmonious gradient of existence with the natural world that once only teased its senses. A special emotional comfort permeates the frame at a heightened level, that I feel I haven't received yet from any narrative driven film to date. Looked with my mind. Felt with my eyes.

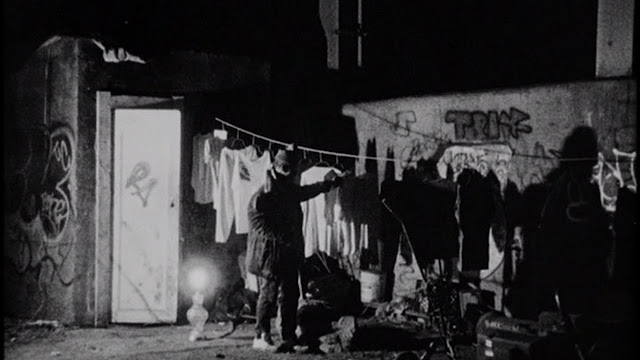

9) DARK DAYS (2000) (Dir. Marc Singer)

Easily ringing as the most economically pertinent film in the bleakest sense, English documentarian Marc Singer's sole directorial effort Dark Days is as much a damning time capsule of the homeless crisis in NYC circa the late 90s as it is a humbling portrait of the depths of human perseverance in the face of a deeply flawed housing system. Adopting a near Wiseman-eqsue approach, the film structures together numerous interviews and verite-like candids to document the unfortunate living situation of New Yorkers who for a few years, called the makeshift shelters tucked deep within the shadows of Freedom Tunnel their home. Originally befriending the main bunch of subjects prior to the making of the film, this foundation of trust ultimately allows for a complete photographic transparency as the subjects let Singer and his camera in on every facet of their day to day existences from rummaging through freshly disposed waste bags for food and showing off DIY housing appliances made from scavenged materials to eventually bearing their vulnerabilities and demons that tragically lead them to their current point. Though, fret not as this isn't some journalistic poverty porn either. Simultaneous to the harsh doldrums is a rather lively character study brought forth by the colorful personalities of the affected, often finding great distraction through supportive friendships and comical banter that beautifully outdo anything that might've been emulated with this topic through fictive means. While as to not spoil, the reasonable questions of motive and ethics that may arise from Singer's rather artful shaping of his one of a kind footage (the film is notably shot on b&w film stock, conveniently bathing the film's topicality in a stylized, gritty filter) is ultimately revealed for reasons that not only reveal a commendable act of character, but take activist filmmaking in literal, productive steps. A frustrating rarity for films of this breed.

8) SUPERSTAR: THE KAREN CARPENTER STORY (1988) (Dir. Todd Haynes)

A longtime recommendation by a close buddy of mine, the banned film of American luminary Todd Haynes left me irrevocably diminished upon first watching, not necessarily out of its obvious tragedy, but from its pitch black commentary on the harrowing consumerist hellscape well integrated into life as a common US citizen. Those familiar with The Carpenters are likely to know the grim fate of vocalist Karen Carpenter, but it is Haynes' on screen materialization of her struggle with and eventual downward spiral due to anorexia via the use of Barbie dolls that reduces the notion of Karen's (and every other consumer's) being as just another material product of society, helplessly pit feeding and consuming until ready to be disposed of. Its didactic use of text cards laid over stock footage of suburbs and supermarkets while the famed hits of Karen & Richard play over hauntingly paint a brutal reality of inorganic complications brought forth by manufactured forces. The instructional mode almost gives off the presentation of a government film or PSA. Haynes ingeniously retextures the narrative of a rise to starry-eyed Hollywood fame as a vehicle to pick at the gruesome toxicity bubbling just beneath the surface of a seemingly stable but heavily processed society. Perhaps "body horror" may be a tad bit insensitive in describing the film, but it's the only label I can think of that even remotely validates what Haynes has singularly achieved here. There are few things more ideologically nightmarish to me as bastard biological threats to one's health that'd otherwise cease to exist in the natural, organic world.

7) OTHON (1970) (Dir. Jean-Marie Straub & Danielle Huillet)

The first of three major director discoveries on this list, the films of French duo Jean-Marie Straub and Danielle Huillet may offer the most daunting challenge in the extreme rigor of their film practice, but for those even slightly interested in literary theory or modernist takes on historical or period texts will find much indulgence in the couple's unmatched filmography. While I could easily just have gone with The Chronicle of Anna Magdalena Bach (1968) or Class Relations (1984), both of which also nearly as strong, Othon adapts the play by Pierre Corneille about a Roman nobleman in search of power through politics and love with a pronounced abstraction in chronological representation. Though the diegetic sphere containing the actors as they appropriately dress and play the part of the text's 69 A.D., Straub & Huillet make a deliberate point photographing their locations to reveal a modern society amongst the backdrop of their classical text. Othon's insular narrative never draws attention to this period agnosticism, but in its very fictive document highlights the timelessness of Corneille's text, its contents being as much a contemporary narrative as it was penned to comment at an earlier period. This fracturing of chronology is achieved so straightforwardly, yet its significance speaks volumes. If more period films tackled their subject with even the slightest iota of transgression as Straub & Huillet display here, this tepid corner of cinema would bore me less than where I currently find it. No more Masterpiece theater type attempts, I beg you.

6) PASSING SUMMER (2001) (Dir. Angela Schanelec)

The second of three directorial revelations is the work of German and noted "Berlin school" luminary Angela Schanelec, represented here by her warm drama of exteriors Passing Summer. Following a shared asceticism in the similar vein of Ozu and Bresson, Schanelec's film rides on hard exteriors opposed to motivated dynamism, birthing a stylized realism scrubbed clean of narrative didacticism (unlike former realist traditions). Composed of a series of long static shots in the loosely plotted but still eventful summer of aspiring writer Valerie and best friend Sophie, Schanelec, with a hidden meticulous groove, observes as the women meander through the sunny season in their own distinctive arcs. Each scene is candid in nature. At many points Schanelec's compositions play more like live action still photos than a cinema that is fully kinetic. But it is at this level where my observations struck as profound. Schanelec isn't vying for any documentation of realist expression. Rather, she merely uses the mimesis of reality to construct a fiction that subconsciously plays for the frame, treating mise en scene as a richly textured film stage for focused performance. Each image does not ask for anything more other than what can be seen and felt. When composed together, the film plays like a recollection of events in one's memory. Minimalism of the highest order.

5) BATTLE IN HEAVEN (2005) (Dir. Carlos Reygadas)

Due to me having already written semi-lengthy summaries for some of the following in recent previous entries, I will remain short for the sake of brevity. Still reeling from the exploitative enigma that is Mexican filmmaker Carlos Reygadas' deeply polarizing follow-up to his more embraced Japon (2002), the suggestively titled Battle in Heaven plays like a bastard child of the best of Andrei Tarkovsky & the worst of Lars von Trier. At once a startlingly bizarre meditation of government worker Marcos' perverse sexual longing for his longtime and marginally younger client Ana (memorably portrayed by Anapola Mushkadiz), Reygadas' adulterous drama succumbs to a violent swerve into explicit nihilism and later desperate spirituality whose unexpected turn is so visceral that I believe one can only bare witness to fully comprehend. In my short time writing, Battle in Heaven remains the most difficult film to internalize and squeeze out into prose. Its power simply resists linguistic communication. Like prayer, what is being mouthed over and over can only scratch the surface of how its gospel is actively processing and signaling out. Interestingly, despite its love and hate response amongst his admirers, Reygadas considers this film to be his personal favorite.

4) THE MOUTH AGAPE (1974) (Dir. Maurice Pialat)

The final of my three major director introductions, the cheekily named The Mouth Agape by French director Maurice Pialat is the one film on this list whose construction fascinates me most. To even possess the tenacity to write a dual narrative of a mother's tragic succumb to terminal illness, confrontation of mortality, and the dreaded grieving process with a despicably comical sex romp is surely deserving of raised surveillance from its source, but Pialat somehow pulls it off with disarming aplomb. I'll be attaching my full observation on it in the links below, but this manipulative command of naturalism is something I still can't wrap my head around. An imminent rewatch may just cement it as a personal favorite, more than it already has for me.

3) COME & SEE (1985) (Dir. Elem Klimov)

Arguably the most well known film on this list, Soviet filmmaker Elem Klimov's definitive mark on the war genre expels just about everything that typically makes me loathe the type of movie in the first place. Simply put, I dislike the advent of war depictions in film. Regardless of the many contexts they may play under, it almost always breaks down to one of two conclusive ends of functionality: barbarism or exploitation. Either war is in some form endorsed as a necessary evil (which it isn't) or its grand scope of violence is visualized as high stakes spectacle. There are of course exceptions to this, but they are incredibly far and few between. Klimov's brutal damnation of the act as the greatest self-inflicting atrocity to humankind by way of unadulterated horror seals the purpose of directly portraying this conflict in the first place. We must never let it occur again, a resounding statement Klimov pleas for, but acknowledges in his film's final moments that as with everything else in the world, endures an imminent cycle.

2) BEAU TRAVAIL (1999) (Dir. Claire Denis)

A self-fulfilling prophecy is how I'd label my now established relationship with French iconoclast Claire Denis' Beau Travail. When first assembling my written list of films to see in high school, Denis' elusive (speaking both to its narrative contents and availability) drama was one of the first few to be added to a roster that has since grown functionally out of hand. At the time having fallen in love with listening to director interviews, Denis and her film engaged a collective mythologizing from their many references as inspiration from filmmakers ranging from Barry Jenkins to Joachim Trier. Waiting for a chance to finally see it, that opportunity wouldn't come until the first day of November 2020 (a lot of firsts here) where finally upon viewing, naturally latched itself onto me, regardless of any prior bias. Mostly wordless in dialogue and actively exiling clear narration, the kaleidoscopic images of French legionnaires in drill routine and eventual combat against the elemental backdrop of Djibouti reverberated a language I am familiar with most. A visual and auditory one. Denis and noted DP Agnes Godard's channeling of the medium's most bare components results in formal validation reaffirming why it is I am drawn to cinema in the first place. Moving images and sounds that matter in sequential composition. What better way to celebrate that than the document of bare bodies moving in all their anatomical beauty and power as they clash with the earthly forces around them. Or better, Denis Lavant losing his shit as the logical conclusion to all that sophisticated rawness.

1) A MOMENT OF INNOCENCE (1996) (Dir. Mohsen Makhmalbaf)

While not a hard truth for me, a strong indicator for myself to know when I've stumbled upon something special is my own immediate submission to its artistry and the subsequent realization of it that follows. For Iranian auteur Mohsen Makhmalbaf's A Moment of Innocence, a delay in that process saw me held so dearly in its graces that I failed to even let its art identify to me until much later during an emotional reprieve. Following a similar interrogation for "truth" in cinema like his close colleague Abbas Kiarostami in this period, Makhmalbaf's search of it is achieved the closest (as of this writing) by realizing early on that such thing is a pretentious idea anyways but still allows for his premise of reenactment to take its natural course, leading to a supremely poetic work of naturalism always playing in the moment, thus creating truthful images just by its brisk, impulsive action. Cinema is only stripped of its innocence when artificiality is given room to creep in, of which this avoids. Funny since its conception is the antithesis to that very notion. The resounding effect of Makhmalbaf's film illuminates brightest as I look back to this past year of watching movies.

Times are tough, but at least we have the cinema.

Links:

No comments:

Post a Comment