The following text is an abridged edit of an academic paper written for a film theory class this fall. My essay's main concern was to identify, illustrate, and hypothesize the place and future of widescale cinematic revolution in an increasingly hostile economic and political climate actively curtailing projects of the such and what small individual attunements could be made to incite change in unmotivated viewing habits. It was written with more of a casual audience in mind, rather than speak to the already initiated, but more than anything it's a personal proof of ideas I've long wanted to tie together and discuss. As a base, Maya Deren's famous "Cinematography" essay is used as a spine for my narrative abstraction. Most of my modifications have cut out in-text citations and removed as much declarative voice to loosen the posture of my discussion for more casual reading (at least as best as I could without having to rewrite the damn thing over). That is all. Hope it inspires something.

-

In 1960, American avant-garde filmmaker and theorist Maya Deren published her seminal essay Cinematography: The Creative Use of Reality where she personally championed for the autonomy of cinema’s exclusive properties within the art of filmmaking. Deren felt a hindrance to cinema consistently sticking to rudimentary form and that in order for the medium to achieve its full potential, filmmakers would have to wholly embrace what the photography of motioned reality and sequencing through montage truly encompassed. Understanding time and space was crucial for manifesting a designated film narrative detached from the trappings of plot, she instead insisted on the manipulation of form via the different tools such as slow-motion, reverse playback, and an overall customization in shooting to take the place of forced expository dullness. Her concerns revolved around the normalization of uninquisitive sculpting, which often saw a replication or simulation of a reality photographed, which she deemed as regressive, “owing nothing” to the “actual existence of the film instrument." Realism, or the perceived notion of it, was for documentarians at best, but certainly not for artists working in fiction, whether live-action or animated. Instead, filmmakers should take advantage of reality by authoritatively imposing their own onto it.

For Deren, it was all about the abstractions communicated within a stitched chronology of images. Much like what she practiced in her own work, her rhetoric is an ideological counterpoint to the aesthetic and narrative traditions commonplace in most productions (her arguments direct mainly towards Hollywood). Aside from just passively photographing reality, which Deren declared as an equivalent to the reality itself, filmmakers should also relinquish the narrative disciplines of literature and theatre and find new temporal linkages from image to image and the sound accompanied. She states that the concept of the cause-and-effect linear narrative was a primitive relic of nineteenth century materialism and in order for film language to be just that, these relationships to other media would need to find complete severance. To kindly elucidate, a film so reliant on reproducing the same effects as other mediums may not be a complete work of cinema at all. Films must forge their own distinct realities to prove their constructs.

Fragments of her arguments find root in earlier proclamations made of similar, philosophic minds. In the Evolution of the Language of Cinema, French film critic and theorist André Bazin acknowledges a similar sentiment, exclaiming the importance of pushing form to breach old traditions. When discussing the advent of sound as a reinvention of the cinema, Bazin notes that with new subject matter demanding new form, “the styles necessary for its expression” must be challenged as a consequence. And for Hungarian film critic Bela Balazs, in his internalized interrogation of the motion picture in his essay The Creative Camera, presents an existential counterpoint to the film image as a reproduction of reality with two pivotal questions of his own. That is, “What are the effects which are born only on celluloid” and which “are born only in the act of projecting the film on to the screen?" The contemplation of which Deren’s case is subject is seemingly not so isolated after all. It seems that prior to her summative gospel, a loosely plotted trend of kindred ideas projecting the capacity for the medium were already taking seed. But whose take on the matter is most considerably pertinent is none other than famed novelist Virginia Woolf who penned an essay dedicated to this observation entitled The Cinema in 1926.

Written as more of a vulgar critique of the medium’s reliance on literature in contrast to Deren’s clinical deconstruction, Woolf’s observations reverberate uniformly. In it she recalls an anomaly experience with cinema during one fateful screening of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) which revealed to her a momentary glimpse into cinema’s lone specialty. During the screening, she writes “a shadow shaped like a tadpole suddenly appeared at one corner of the screen… It swelled to an immense size, quivered, bulged, and sank back again into nonentity. For a moment it seemed to embody some monstrous diseased imagination of the lunatic’s brain. For a moment it seemed as if thought could be conveyed by shape more effectively than words. The monstrous quivering tadpole seemed to be fear itself , and not the statement 'I am afraid." Woolf learned later that this strange animated tadpole was simply an accidental burn in the print, but its revelatory impact remained, so much that it was the catalyst for Woolf’s write-up. Her revelation, from the viewpoint of an artist working in literature, powerfully resounds the distinctive manipulations of what film can do that words cannot. The reality before her in that brief moment belonged to cinema and cinema only.

To defend the notion of autonomous film language, the psychology of how our brains receive, transmit, and process information as it is laid before us is important. Natural to our development, starting around the ages of three to four, we begin to organize sensory stimuli from the world around us and arrange its information into chronological sequences. These are known as episodic memories. A narrative construct in relation to ourselves. This ability is what allows us to abstract the plethora of variables in our lives and form coherent narratives as an intrinsic link to our conscious ties to time as we traverse in parallel along its linear plane. So while one could most certainly see the relation of cinema’s development and its nearly universal sense of perceived narrative form in dedication to the continuity style as an interwoven relationship, the actual functionality of linearity is not all that key when personal abstraction and emotional projection are taken into account.

But first, in narratology, the importance of the monomyth must be recognized and detailed in its widely utilized and perceived cultural effect. Most pertinent to literature and subsequently film is Joseph Campbell’s A Hero’s Journey, which is a modern cultural summation of ideas originally pledged in Aristotle’s Poetics. As Campbell describes the myth himself in his book The Hero with a Thousand Faces, “A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man." Due to cinema’s early outsourcing to literary material as it pertained as a vestigial byproduct of theater, Campbell’s monomyth has since seen an infiltration to the development of film narrative and thus film language. Many films have followed this arrangement of dramaturgical events (or some slight deviation of it) across a span of different genres since the birth of cinema. From The General (1926) to The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974) to Toni Erdmann (2016), the core narrative structure remains synonymous. This form of linearity as a result leads to Deren’s critique of its prognosis to the medium. Though for as commonplace as the structure is within film, its functionality is entirely subjective.

Ultimately the role of which Campbell’s monomyth, or any given structure alternatively, plays into the mind of the spectator is trivial to their processing of a particular film. Rather, how any film is encoded and decoded is dependent on variables much more nuanced and abstract to each individual’s reception. A viewer can be conditioned to recognizing and attuning to familiar structures, but how the material is interpreted is traced within the imagination as it reacts with and against a filmmaker’s directive lead. Therefore, while classically ingrained structures like Campbell’s monomyth that in typical also simulate, to a degree, the human sensory system’s chronological arrangement of events in dynamically linear form, how any film transmits and effectively renders has no primary bias. Meaning, the manner of how a filmmaker constructs their narration and what a spectator does with it is open for attuning. By this metric, Deren’s considerations prove entirely doable. It is then just a matter of negotiation for both parties. For filmmakers, the reconfiguration of their cinematic language and for audiences, the will to readjust accordingly. Also relevant are the sociopolitical and cultural factors to determine what is made of such innovations. Education, class, and identity will drive what is accepted and what isn’t. The major role of capitalistic influence as it relates to cultural tastemaking (i.e. your sleuth of recycled intellectual properties and their saturation in advertising) also has a lot to do with how audiences are guided in their media consumption, thus pivotal in the shaping of insight, but more on that in a bit. Overall, the possibility for this embrace of aesthetic and narrative shifting are in place.

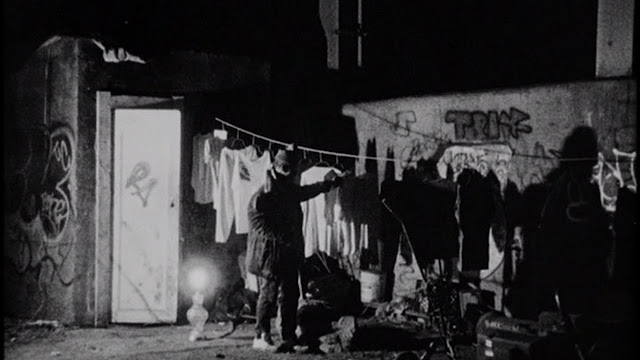

Deren’s theory is ancillary to a developing postulation I’ve been sitting on in the past year, which expedites further pushing these notions purely out of the sake of cinema’s survival in a media landscape grown long stagnant. With film now having left the exclusivity of the theaters and into the homes of the populace as a result of online connectivity since manifested as an integral part of communicative technology, the consequences of over saturation have grown to be a true concern of mine. In a world where cinema’s properties have expanded into television, online video sharing, and brand advertisements, the need to advance the artistry of film has never been more dire. When chewing gum commercials and social media content creators successfully simulate and yield similar aesthetic, and to an extent, dramatic results as those in the cinema, a dark cloud looms over the eventual fate of that original medium’s prognosis to antiquation. Jean-Luc Godard shares the notion as he once eluded to in a 2011 interview for his (then) new film Film Socialisme (2010), fittingly a work rebelling against conventional narrative forms. In the interview, Godard notably, though with some cheek provocation, declared the film auteur as “dead” and therefore, the cinema was too. In his own words, “with mobile phones and everything, everyone is now an auteur.”

With democratization, a double-edged sword manifests. It serves graciously for the marginalized, but thereupon creates new, if more troubling, scenarios for artistic revolution to prevail in a prominent mainstream setting. Much of it due to the vast power of upper class influence and the corporate sector. The permeation of more screens in society results in more filmmakers creating work. But when filmic output is churned out in unprecedented numbers, in ways unfathomable to the cinema’s purpose upon conception, at a certain point, that sheer abundance will in turn dilute the power of the images and render them expendable. With familiar film images and narrative forms (now) being exploited across many different canvases, it’s no wonder the cinema has lost its popularity as an experiential forefront. Why dedicate time and money to a movie when its assets have become so open source? Factoring in the target demographic (and majority) of the working class’ opportunity costs, oscillating between how and where to spend one’s limited resources, the cinema is too much of a bourgeois affair to dedicate one’s waning attention to given its practical irrelevancy. Placing the reality of strict monetary investment aside, which differs on the basis of each project’s capitalistic circumstances, it is an appropriate opportunity for filmmakers to experiment with their imaginative minds and opt for each’s own re-inventive take of cinematic communication.

Due to the nature of financing and distribution for getting films made and seen, it is also a risk that lies just as much in the hands of producers, financiers, and distributors as the filmmakers themselves. This is where artistic risk often falters before getting the chance to flourish. Understandably, when film is treated as business, yielding the highest possible return in investment is the sound ambition to be met, but as the market continues to chase higher stakes and most films struggle to be lucrative, let alone profitable, these unattainable expectations need reevaluation. With Hollywood studios relying more on recycling familiar intellectual properties due to their refined track records of financial success at the box office, more money is being sourced individually for these types of projects than ever before. This shift has come to see the mid-level budget film obscured into endangerment and most significantly, lesser control in the hands of artistically forward filmmakers. Either a studio spends minimum funds on a smaller project (who typically receive less advertising, thus yielding smaller audience numbers) or goes all out on a few major productions, better known as the tentpoles. It’s an incredibly unhealthy tactic financially speaking. There’s also much blame to be placed on larger economic and political factors.

To discuss the cumulative impact of the “mainstream,” acknowledging and criticizing the United States’ global media stranglehold is necessary. The ruling class and corporate elite’s diseased infatuation with greed as hierarchical hedonism and its subsequent relationship with eliminating advanced literacy of the populace as an act of suppression to feed such corrupt systems is the root cause for cultural stagnation. For this reason, delving into the ties between this agenda to its influence on national media is most critical to seeing Deren’s aims realistically see the light of day. A mass lifting of intellectual independence and agency would have to occur to allow for the adoption of experimental aesthetics and narratives to prosper. The problem is, such a thing is a slippery slope to effectively hindering the lucrative profits of the products who exist in large part to be consumed with minimal brain work and regurgitated in the form of franchising and merchandise. In contrast to other filmmaking cultures, film in the U.S. is and was never about artistic accomplishment, but what could merely be sold, to how many people, and for how much (the more the merrier). Cinema being treated as a vessel solely for capitalism dilutes its potential for inner growth. Until this changes, the medium stays in stagnation, merely a tool to keep mass audiences obedient. A cultural purgatory of sorts.

Though cinema has certainly undergone revolution since Deren’s text, our relationship with it hasn’t, at least not intellectually. Cinema of reinventive conceit remains, for the most part, as marginalized and fringe as it was during the many independent and avant-garde movements occurring during Deren’s period. So where as new radical languages have developed, they’ve only gone so far as to incite minor, often local, cultural shifts. Remaining largely uninitiated in any broader social context. Where Deren vouched for ontological remodeling of the creative, I now presently vouch for our own as audiences. To begin, we must first remove our core biases of linearity and classical dramaturgy and get in touch with our own perceived notions of symbols, stimulation, and our emotional intelligence. Hypothetically, one cannot propel their relationship with the moving image until this realignment of expectation and process occurs. Like any other art we may experience, whether a performance of dance or spectating a painting or sculpture, it is about how we exchange wavelengths with the piece itself. Treating a film as such will yield an immediate difference in interactive posture. Take confidence in how to process the motion picture.